For an enhanced digital experience, read this story in the ezine.

How today’s environment is shifting our thinking about the future of the profession

Much has changed since NRPA published its Park, Recreation, Open Space and Greenway Guidelines in 1996. In those simpler times, park and recreation agencies focused on things, like playgrounds, ball fields, boat ramps and youth athletics. Now they’re also involved in socioeconomic and environmental issues, such as the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, wildfires, urbanization, social equity and services, habitat restoration and economic development.

In recognition of these increased complexities, there are no longer any nationally accepted standards for parks and recreation planning. Each community must determine its own standards, level-of-service (LOS) metrics, and long-range vision for its parks and recreation system based on community issues, values, needs, priorities and available resources. Even NRPA’s 1996 guidelines recognized that “a standard for parks and recreation cannot be universal, nor can one city be compared with another even though they are similar in many respects.” Therefore, it’s time for a new approach to parks and recreation system planning; one that not only addresses traditional park and recreation challenges, but also is robust and comprehensive enough to address these broader community-wide issues.

First, we need to broaden our perspective of parks and recreation systems, in order to respond to societal shifts and expectations in a meaningful way. Parks and recreation facilities should no longer be regarded as isolated, but rather as elements of a larger, interconnected public realm that also includes streets, museums, libraries, stormwater systems, utility corridors and other civic infrastructure. Alternative dimensions of parks and recreation systems, such as equity and climate change, should be considered from the onset of the planning process. And, each site or corridor within the system should be planned as high-performance public spaces (HPPSs) that generate multiple economic, social and environmental benefits. This broader perspective encourages park and recreation agencies to transcend their silos — and leverage their resources — to plan and collaborate with other public and private agencies to meet as many of the community’s needs as possible. As a result, parks and recreation systems can be repositioned as essential frameworks for achieving community sustainability, resiliency and livability.

Second, we need to replace the traditional linear, narrowly defined parks and recreation system master planning (PRSMP) process with a cyclical, open-ended process that is constantly updated and integrated with other foundational public realm plans, such as long-range transportation plans, stormwater master plans, habitat conservation plans and future land-use plans. Such an ongoing, collaborative planning process can lead to the development of an integrated public realm that can generate far more benefits for a community than the traditional siloed parks and recreation system. This proposed new approach, illustrated in Figure 1, differs from the traditional approach in several ways.

Project Initiation, Planning and Dimensions

A noteworthy difference between the traditional PRSMP and the proposed new approach is the amount of time and thought given to the initiation and planning phase of the project, including the development of a project charter, project plan and a readiness audit. Careful and thoughtful planning is critical to identifying opportunities to generate greater resiliency and sustainability benefits for the community, as well as building the credibility and support needed to implement key recommendations. The eventual success or failure of many plans can be traced to the amount of time spent initiating and planning the process. Once a PRSMP process begins, it is very difficult to change its scope, budget and deliverables midstream.

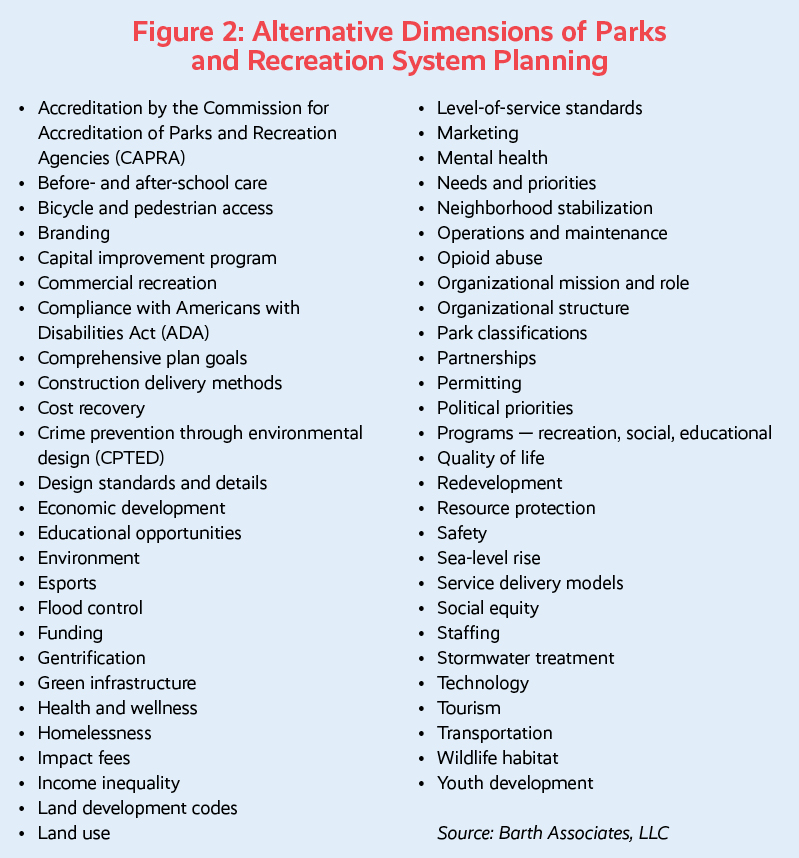

A key component of the initiation phase is the identification of the desired, alternative “dimensions” of parks and recreation planning to be addressed during the process, as listed in Figure 2. Identification of these dimensions during the initiation phase has direct implications for the makeup of the project team, the scope of work, the areas of focus and the eventual success of the project.

Decision-Making Framework

Another feature of the new PRSMP approach is a more thoughtful and nuanced “decision-making framework” to replace absolute standards and classifications, providing parks and recreation agencies with the freedom and flexibility to respond to community issues and needs. Such a framework may include: the agency’s mission and vision; agency and community values; guiding principles; residents’ needs and priorities; community context; desired experiences; and service-delivery models. Collectively, these components encourage thoughtful, context-based solutions rather than pre-conceived standards.

Feedback and Consensus Building

The new approach provides numerous opportunities throughout the planning process to pause, present and discuss interim findings; determine if additional lines of inquiry are needed; and build consensus with key stakeholders and decision-

makers regarding the direction of the process. Typical formats (online or in-person) often include staff review meetings, stakeholder focus group meetings, advisory committee presentations, and one-on-one briefings and workshops with elected officials. Such feedback loops are critical for eventual approval, adoption and implementation of the master plan.

Evaluation of Existing Conditions

While the traditional approach to evaluating existing conditions focuses solely on parks and recreation facilities, the new approach also emphasizes the evaluation of the specific dimensions identified in the initiation phase. Each topic requires an in-depth analysis of existing conditions and issues, and their implications of the parks and recreation system. For example, research and discussions with the public works or engineering department may reveal new information, such as the need for additional stormwater treatment or floodwater storage in certain areas of the community or the opportunity to meet recreation needs and stormwater needs on the same site. Investigation into crime rates and safety issues could identify hot spots that might benefit from additional security, nighttime recreation programs, or design modifications in accordance with guidelines for crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED). Parking and transportation issues could be investigated to determine the potential role of parks in providing trail connections, bike-share stations, overflow parking, transit stops or other multimodal transportation solutions. What’s more, discussions regarding housing and economic development could detect opportunities for parks and green spaces to stabilize neighborhoods, improve property values and catalyze redevelopment.

Preliminary Implementation Framework

The purpose of the preliminary implementation framework (PIF) is to initiate implementation discussions as early in the process as possible; traditional processes often leave implementation discussions for last, which can doom the project to failure. The PIF is particularly important for plans that address numerous dimensions, such as transportation, stormwater and social services, which will be implemented by agencies other than a parks and recreation or planning department. In addition to traditional forms of implementation — such as capital improvements, additional staffing, new programs and increased maintenance — the PIF may include updates to comprehensive plans or land development regulations; partnerships with other agencies, businesses or nonprofit organizations; changes to staffing or organizational structure; refocused delivery of programs and services in response to the agency’s mission or residents’ priorities; and changes to maintenance and operations procedures. Accreditation by the Commission for Accreditation of Parks and Recreation Agencies (CAPRA) is another form of implementation.

Needs Assessment Process

The new approach proposes a more rigorous, scientific methodology than that used by many communities. Needs assessments are often scrutinized by the public, stakeholders and elected officials; parks planners need to be able to defend their methodology, data collection process and findings. If done correctly, a needs assessment is a type of applied social research that involves developing a research design, gathering and analyzing the data collected from various sources, and using the results to inform policy and program development. In our practice, we use a mixed-methods, triangulated approach that compares the findings from quantitative, qualitative, and secondary research techniques and data to identify top priorities. As with the evaluation of existing conditions, the needs assessment process should solicit public input regarding the entire public realm, as well as community-wide resiliency and sustainability needs.

Level-of-Service Standards

The 1996 Park, Recreation, Open Space and Greenway Guidelines state that “we must realize an open space standard is not so much an exemplary measure to be used in some form of comparison or judgement of adequacy or accomplishment, but is an expression of a community consensus of what constitutes an acceptable level of service.” Therefore, the new approach encourages public agencies to revisit their core values, principles and goals; and to develop LOS metrics that effectively reflect their aspirations. In addition to the traditional park metrics of acreage, access and facilities, for example, some communities may also wish to establish new metrics related to resiliency and sustainability as outlined in Figure 3.

Collaborative Visioning

As mentioned above, a key attribute of the new approach is the collaborative planning of the park and recreation vision concurrently with planning of other public realm elements, such as streets, bikeways and trails, civic spaces, stormwater treatment facilities and utilities.

Collaborative planning is also required to address broader community-wide dimensions, such as health, equity and economic development. Strategies to increase collaboration includes concurrent scheduling of PRSMPs with other foundational public realm plans, such as comprehensive transportation plans (CTP) and stormwater master plans; concurrent, multidisciplinary needs assessment processes — including site visits, interviews, focus group meetings, public workshops and surveys; and multiagency and multi-departmental reviews of proposed capital improvements to identify opportunities for partnerships, collaboration or joint use. Collaborative brainstorming by people with different perspectives and backgrounds often can yield far more innovative and imaginative ideas than can visioning that involves only those of similar mindsets.

Implementation Strategy

The implementation phase of the PRSMP represents the culmination of all the analyzing, planning, ideating, discussing, meeting, surveying, thinking and visioning activities described above. Consistent with the previous phases of the planning process, the new approach to PRSMP emphasizes a collaborative approach to implementation involving community leaders, elected officials, multiple departments and agencies, businesses and other key stakeholders. An effective implementation strategy requires that participants transcend the silos of their departments or agencies; identify opportunities for partnerships or joint use; leverage available resources, regardless of the source; and actively look for ways to generate multiple benefits for the community through implementation of projects, programs and initiatives.

Embracing a New Approach

Regardless of your aspirations — whether you wish to transform your entire community, reposition your department or parks and recreation system as being more essential, or simply increase the quality of the services and programs you provide — the new approach to parks and recreation system planning can help you meet your goals. Following this process will result in a PRSMP that is more relevant to the needs and issues of your community and elected officials, more collaborative, more credible and more likely to be successfully implemented and transformative. And, adoption of this new approach can yield numerous benefits for park and recreation agencies and their communities, including increased recognition, quality of life and resiliency.

To hear David Barth speak about PRSMPs, tune in to the November bonus episode of Open Space Radio at nrpa.org/NovemberBonusEpisode.

David Barth is the Principal of Barth Associates, a firm specializing in parks and recreation system planning (david@barthassoc.com). He is the author of the new book Parks and Recreation System Planning: A New Approach for Creating Sustainable, Resilient Communities