Latin crosses, the traditional symbols of Christianity, have had a long association with publicly owned places, especially parks. Throughout much of the 20th century, such crosses were erected without serious concern they may violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment of the Constitution, namely that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion….”

In practical terms, when it comes to monuments with religious symbolism, the Establishment Clause has meant that no such religious monuments shall be placed, or allowed to remain, on government-owned property. To do so would give the appearance or symbolize the reality that government favors one religion over another. It is a simple and straightforward prohibition. However, over the past century, there have been dozens of Latin crosses or other monuments with religious symbolism erected in parks and public plazas, and their presence has led to literally decades of litigation to remove them, alter them or transfer the land on which they sit to non-public owners.

Courts have issued conflicting interpretations regarding this bedrock constitutional principle, and those not of Christian faith have objected strenuously that such symbols are harmful and impermissibly relegate non-Christians to a lesser status. Groups, such as the American Humanist Association and the Freedom from Religion Foundation, have sued to have such crosses removed from their publicly owned settings, prompting outpourings of civic pride, because, over the decades, the crosses have come to have cultural, historic and even economic value from tourism. Some communities have dug in to keep such crosses in their original locations and have even fought against the simple solution of transferring the land to non-governmental entities.

A Secular or Religious Symbol?

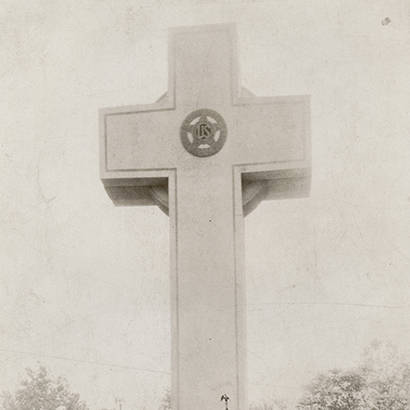

The most recent case of crosses in parks to come before the Supreme Court involves the 40-foot-tall Peace Cross that sits on a sliver of public parkland, owned by the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (MNCPPC), amid highway intersections in Bladensburg, Maryland. As Professor James Kozlowski of George Mason University describes in his Law Review column on page 32 of this issue, this case of a Latin cross on public land in Maryland hinged on whether the Peace Cross was primarily a secular symbol that, first, did not violate constitutional norms, second, did not advance or inhibit religion and, third, did not foster an excessive government entanglement with religion.

The Supreme Court decision allowing the Peace Cross to remain in place surprised some court observers. While the 7–2 vote indicated a significant majority of the court was in favor of it remaining, seven judges wrote separate opinions of widely diverging points of view. In Justice Ginsburg’s forceful dissent, she wrote “Just as a Star of David is not suitable to honor Christians who died serving their country, so a cross is not suitable to honor those of other faiths who died defending their nation. Soldiers of all faiths are united by their love of country, but they not united by the cross.”

Adrian Gardner, general counsel of the MNCPPC, said in an interview following the decision: “Our planning board took a courageous stand. Part of our original reason for being [a park and planning commission] is our preservation purpose. Our case was strong. This cross was not built with a religious purpose in mind.” He went on to emphasize what was a crucial point in their defense about the original intent of historic memorials and monuments and how perceptions of their meaning can change over time. “I kept telling people ‘Remember the Alamo.’ That historic site was originally a Catholic church and is now operated by the National Park Service as a National Historic Monument. Today it has a new meaning. Symbols can change over time and serve other purposes.”

Perhaps, that is why many communities will fight to keep crosses in their original historic location and context. The Mount Soledad cross is another large Latin cross built atop the highest point of a hill with a commanding, spectacular view of the city of San Diego and surrounding landscape. The original cross dated from 1913, but the most recent cross, a large stucco cross that’s 29 feet tall, was erected in 1954 to honor Korean War veterans. It sat not in a park, but on land owned by the Department of Defense. After 25 years of continuous litigation, the parties to the suit agreed to a resolution in which the cross and the immediate land around it were sold to a private nonprofit foundation, while the surrounding land became Soledad Natural Park of the City of San Diego. Access to the memorial is through the park.

The fate of a large wooden cross at the top of Black Rock Mountain, elevation 3,000 feet, in rural Rabun County in northeastern Georgia, became a matter of fierce civic pride after the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sued because it was located in the middle of a state park campground. “It united this community like nothing before,” said Bill Jarret of the Chamber of Commerce in an interview with The Washington Post in 1979. “Never in our wildest dreams did we think anyone could object to a cross on a mountain,” said Jarrett, executive director of the Rabun County Chamber of Commerce. Over the years, when the cross fell, citizens were not allowed to replace it. However, a new cross was erected in 2009 on Black Rock Mountain on land owned by the Raburn Cross Society.

In San Francisco, a cross known as the Mount Davidson cross that’s more than 100 feet tall was erected, with a clear Christian intent, on what was originally private land. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, via the press of a telegraph key, lit the Mount Davidson cross from the White House in 1934, a few days before Easter. Visible from many viewing points in the city, the Mount Davidson cross sits in the middle of 20 acres at the top of a hill on land the city eventually purchased for a public park. Easter sunrise services were held from the cross for decades and even broadcast from the park in the 1950s and ’60s.

Eventually, the religious purpose of this cross was seen as improper on government-owned land, and the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Jewish Congress and Americans United for Separation of Church and State sued the city for its violation of the Establishment Clause. The cross was ruled illegal in 1996, and, in 1997, the city auctioned off a half-acre of land on which the cross sat. That half acre was acquired by the Council of Armenian Organizations of Northern California, which installed a plaque to memorialize the victims of the 1915 Armenian genocide. By court agreement, the cross is lit two days per year.

In Pensacola, Florida, a suit brought by the American Humanist Association and joined by the Freedom from Religion Foundation, asserted that a Latin cross that’s been standing since 1941 in Bayview Park, violated the Constitution and must be removed. A federal district court judge declared this cross unconstitutional in 2016, a decision that was upheld by a federal appeals court in 2018. In response to a question if non-Christians in the community object to the cross or if there is general acceptance for its historic and cultural value, the city replied: “The current city administration is not aware of any objections to the cross had been raised prior to this lawsuit. Again, the city’s position is that the Bayview Cross is a valuable part of our history, and we feel that our efforts to defend the cross reflect the overall sentiments of our community as a whole.”

It is uncertain what impact the Supreme Court decision on the Bladensburg Peace Cross will have on the cross in Bayview Park. Representatives for the city are continuing to work to keep the cross at its current location in Bayview Park, as the city awaits a new ruling from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. The cross, they say, is a valuable part of Pensacola’s history and sense of community at the park.

Whether the Supreme Court decision on the Peace Cross continues to reverberate through cities and states that have other monuments and memorials with religious symbols remains to be seen. It is not surprising to note that parks are often at the heart of some of the most important First Amendment issues our nation faces. Parks are a place where our values and principles as a democracy are shaped and the crucible in which they are forged. The exercise of our unalienable rights — life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness — and the continuing issues of freedoms at the heart of our democracy will continue to be defined by the public spaces we know and value — our public parks.

Richard J. Dolesh is NRPA's Vice President of Strategic Initiatives.