In merging nature and culture the most successful cities combine such universal needs as maintaining or restoring contact with the cycles of nature, with specific,

local characteristics. – Sally A. Kitt Chappell, Chicago’s Urban Nature: A Guide to the City’s Architecture + Landscape

In the 21st century, our parks and green spaces are how we are still able to connect, on a primal level, to the purity of nature. Parks have public health, preservation and conservation implications — from providing places for physical activity and offering safe spaces for children to play, to helping to lower crime rates. And, their aesthetic value is also a source of civic pride. In short — as we all know — our parks are vital to our communities.

Millions of acres of land in the United States are devoted to our local, state and national parks. More and more are opening all the time, but there’s still more work to be done to preserve green, open spaces. Innovative projects designed to transform unusual public spaces are being started across the country. However, can any community undertake these kinds of projects? If so, how do you turn an idea into a park?

Getting Started

While there are certain common starting points for everyone, the route to get from idea to park is unique for each project.

“Typically, a park project gets started through a demonstrated need from surveys of community members, and other public input that is incorporated into the city’s Comprehensive Plan and the Parks and Recreation Open Space (PROS) Plan,” explains Mark Harrison, landscape architect with the Parks Planning and capital development manager for the city of Everett, Washington, Parks & Community Services Department. “Park property donations and park construction for new land and housing developments are also negotiated with city officials and are included in a development agreement.”

Depending on the scope of the project, it can either be a straightforward process or be complex and full of intricacies. Most new projects begin with the community members who usually are the first ones to recognize the need and desire for a new park. From there, a project can go any number of directions.

“It really does depend on how big the project is going to be,” says Bill Lambrecht, superintendent of Parks and Planning for the city of Wilmette, Illinois. “For a new site, typically, we are approached by residents asking us to acquire [property]. For example, the suburb we work in is virtually all residential and there is very little open space left. When a parcel becomes available, residents usually ask us to keep it open as opposed to it being developed for single or multifamily dwellings.”

It is at this point that funding starts to play a part. Nothing can be done — no matter how altruistic the endeavor — without the funds to pay for the land. Here, those involved in the project can begin to employ some creativity. There are traditional funding methods and then there is the option of finding partnerships with local, like-minded organizations, such as the YMCA or local school and library districts.

“Our two most common ways of obtaining parkland is through purchase or as a dedication in satisfaction of parkland dedication requirements through the city’s development process,” explains Jenny Baker, Parks, Planning & Development manager with the city of McKinney, Texas. “Funding depends on the size of the park and may take several budget years. Once we hire a consultant to design the park, we hold public input meetings to find out the needs and wants of the park users and adjacent residents and specific user groups.”

The Plan

With the funding in place, the real work begins. The park has to be conceptually designed, construction plans need to be drawn up and the actual building of it needs to be opened up to the public for bidding. There are a multitude of steps along the way and each is critical to ensuring the project is successful.

“The plan is often formulated through a series of steps,” says Jeffrey Richards, a registered landscape architect and parks planning coordinator for Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. “The initial concept may start simply as a collection of words that encapsulate the desire for a specific park, sometimes speaking to the special natural resources worthy of preservation or the community’s needs for recreational opportunities.”

These often nebulous plans must be fluid. The project has to fit into the actual physical space of the property being eyed. Frequently, plans have to be adjusted to match the realities of the land available, the political landscape or just random occurrences that crop up during this planning phase.

“Getting the public involved has always worked in our favor,” Lambrecht says. “The only time there is an issue is when residents do not pay attention to press and other forms of contact and then say they were uninformed. [Large-scale projects] like I have been involved in recently have us sending a first-class letter to every household in town, in addition to reaching out to local press and including the information in our quarterly brochure.”

Crossing the proverbial t’s and dotting the proverbial i’s require a lot of moving parts and a lot of specialized professionals and laypersons. The master plan is often a broad stroke snapshot of the project, outlining specific details and the overall physical attributes and dimensions of the park project.

“Our most recent example of a park project was a 17-acre site that was owned by a local university and that they decided to sell to a developer,” Lambrecht continues. “The residents in the area did not want a densely developed parcel adding to traffic, and they did not want to lose the open space they were all use to using at that location. The process ultimately took five years, from the property going on the market to the referendum, closing on the property and sale of the building to the Village and then the developer. All the while, planning was underway for the park. Renovation of the building, including the community center space, was being completed while the park was being developed.”

“Because it is to be a ‘public’ park, many people can be involved, although the level of public participation varies from project to project,” says Richards. “A local ‘champion’ is a unique player and a treasure really. This is a person that provides the energy and drive to get other people moving in the development of a new park. They keep at it, regardless of roadblocks and delays, and they are invaluable.”

“Parties to be involved are identified in each project’s scope questionnaire, and that can change throughout the planning process,” explains Harrison. “Unique players may include Native American tribe representatives, utility company representatives, travel and tourism professionals, scientists, engineers, school district members, planners and maintenance professionals who are stewards of similar public and private park facilities, chamber of commerce members, police department specialists and special committee groups, such as, in our case, the Downtown Redevelopment Commission.”

Later in the planning process, technical specialists become involved. These include land surveyors, landscape architects, civil engineers, attorneys and, of course, contractors. All of these people have their own ideas and opinions about what is best for a project, and it can become difficult to push goals through. It would be easy for many projects to simply die before ground is even broken; however, it is at this critical point that “magic” often happens.

“The best practice that I always employ is to listen,” Baker advises. “During the planning process/public input process, we have found that listening to the residents and trying to incorporate as many of their requests, ideas, etc., is extremely important. Even the smallest of things make a difference.”

With so many different entities involved, hurdles of all kinds are bound to exist. These can range from bureaucratic contingencies to environmental concerns. Everyone consulted for this piece echoed Baker’s philosophy that the simple act of listening is the best way to overcome these problems.

“You need to always be willing to listen,” Richards emphasizes. “This doesn’t just include [listening to] the residents. You need to also ‘listen’ to the land. Spend an extended time there across every season.”

As anyone who has ever shepherded a park planning project from beginning to end can attest, it can be a long and often arduous process. The larger the project, the more complex and the more time it can take.

“Projects that include grant applications can add an additional year,” says Harrison. “City budget allocation and approval can add three months to a year. Project design, bidding and construction document preparation can take six months to two years. Construction itself can take between three months to two years.

“A recently completed large park project with which we were involved, generated $2.5 million in construction costs, from the consultant selection to the final contractor payment, and spanned a period of eight years.” On the other hand, small projects that cost around $25,000 in construction fees can be completed in as little as one year.

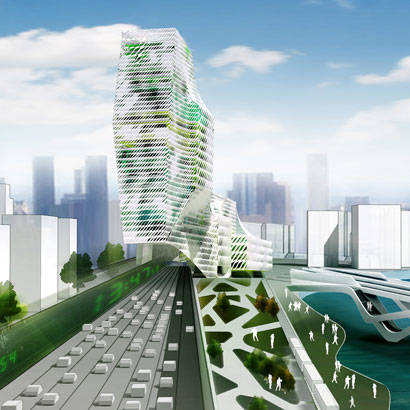

Despite the time, hours and frustrations that come from these large projects, the best part is when they finally open. In this era, as more people are being creative in finding ways to best use the land and resources available to them — such as converting former landfills, vacant lots and abandoned buildings into parks — and trying to best serve the growing elderly segment of our population and simultaneously serve the growing youth segment, unique ideas and situations present themselves every day.

Conclusion

Turning formerly unused spaces, especially in urban environments, into parks offers both challenges and unbelievably satisfying rewards. Transforming a bleak area into a place of public beauty is something truly special.

Parks go beyond the grass, trees and recreation equipment they comprise. They become integral parts of people’s lives and essential parts of a community. They bind people together over their shared love of the outdoors and their desire to see beauty in their neighborhoods.

President Lyndon B. Johnson, perhaps, said it best when he talked about the need to preserve public land: “If future generations are to remember us with gratitude rather than contempt, we must leave them something more than the miracles of technology. We must leave them a glimpse of the world as it was in the beginning, not just after we got through with it.”

Eric Moreno is a Freelance Writer based in San Antonio, Texas.