The harmful effects of certain species of algae on people and animals have been known for over a century. Such algae is found virtually everywhere, but in recent years, cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, have been found in dense concentrations in public park recreational lakes and ponds.

Cyanobacteria in concentration produces cyanotoxins, which are powerful neurological poisons that have been linked to a variety of illnesses in humans and pets, including documented deaths in wildlife and pets. The most recent concern is that dogs that swim in water that contains the blue-green algae may ingest fatal amounts of the cyanotoxin poison by swallowing water or licking their fur to clean themselves after swimming.

Tragic deaths of beloved dogs have occurred recently in public recreational lakes and ponds in North Carolina, Texas and Georgia, from suspected poisoning from blue-green algae. In addition, large outbreaks of blue-green and other toxic algae, known as Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs), have been found in Mississippi, New Jersey, the Pacific Northwest, the Great Lakes and many other locations across the United States. The recent identification of cyanobacteria in New York City’s Prospect Park and Central Park have shown that the threat of cyanobacteria poisoning is not just a threat from rural ponds and large lakes.

While such microalgae are found virtually everywhere, certain environmental conditions such as heat, water stagnation, and excess nutrient loading can trigger the explosive growth of such potentially dangerous algae. Mid-to-late summer is most often the time that such Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) can spread with astonishing speed in lakes, ponds and along beaches. The proliferation of cyanobacteria in water bodies in public parks poses a significant threat to public and pet safety. Park and public lands managers need to be especially aware of the potential dangers during this period of highest risk.

The most common genus of algal bloom-forming cyanobacteria in freshwater bodies according to the EPA is Microcystis, and it is almost always toxic. According to Richard Lacouture, assistant research professor at Morgan State University in Maryland, who has studied phytoplankton and algae in the Chesapeake Bay for more than two decades, cyanobacteria can commonly be found in almost all freshwater bodies, but it is also the easiest to detect.

“By far, the most impact it has is on animals. It’s about ingesting the toxin,” said Lacouture.

This means that dogs are at a high risk, but it is also not safe for adults or children to swim in or have contact with the water where it is present. Park workers who have frequent water contact may also be at elevated risk.

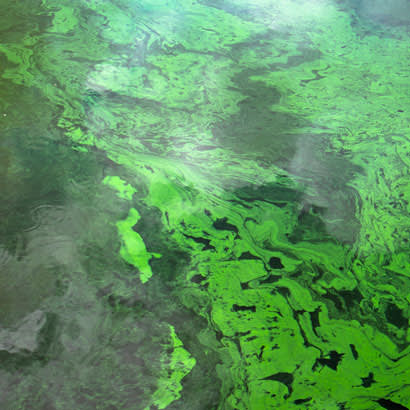

For park managers, identifying such a threat as early as possible is of paramount importance. Lacouture says blue-green algal blooms are usually obvious because of the highly visible appearance of the algae on the water surface.

“It looks like someone took a can of green paint and poured it over the water,” he said.

Lacouture says if you see this condition, it is time to get your water tested and to be vigilant about preventing water contact by pets and people. Testing for toxicity, he says, is something that cannot be done outside of a lab. The cost is relatively inexpensive and, “it’s better to be safe than sorry.”

Where do you get water samples tested? This is something that all agencies need to learn for themselves — it may be your city or state health department, it may be your state department of environmental resources or it may be a private lab. Each city, county and state have different organizational structures and responsibilities for environmental contaminants. It is up to you to learn who is responsible, and it is better to be proactive than to wait until you have a crisis and you don’t know who you should be contacting.

Lacouture says that park staff need to be aware and alert of the hazards of potential water contact where cyanobacteria are known to be present. Self-education is important, as is making sure all staff know what to look for and when to report suspected outbreaks. Microcystis is not the only toxic microalgae, he notes — others may be present and less obvious in the water column, but blue-green algae is the most important to look for.

With regard to allowing water contact by pets or people, it is important to remember that you don’t know where the safety threshold might be. It may temporarily be safe in one area, but the presence of cyanobacteria is largely determined by surface water conditions and wind will move it from one area to another.

If you have an outbreak of blue-green algae this year, don’t become complacent, says Lacouture. The algae can overwinter, and it might be back the following year. Preventing the occurrence of blooms is better than trying to remediate existing blooms. Strategies include reducing inputs of nitrogen, and especially phosphorus, a key component of agricultural and landscape fertilizers. One simple method for small bodies of water shows surprising promise, says Lacouture — placing bales of barley straw in ponds. Barley straw has been shown to help control a number of species of algae, and it may also contribute to reducing the presence of blue-green algae.

The bottom line is if you have an outbreak of blue-green algae, take it seriously, act proactively, and work with your city, county or state department of environmental health on long-term strategies to control and eliminate its presence.

For more information on identifying and managing harmful cyanobacteria in public lakes and ponds as well as much other useful information, visit EPA’s webpages.

Richard J. Dolesh is NRPA’s Vice President of Strategic Initiatives.